📛Thai Names & Titles

Understanding naming conventions and proper forms of address

Understanding naming conventions and proper forms of address

My first week working in Bangkok, I called my colleague "Mr. Wongsakul" during a meeting. The room went awkwardly silent. Later, a friend explained: I'd just committed the Thai equivalent of calling someone by their social security number. His first name was Somsak—that's what everyone called him, from the CEO to the security guard. His surname, Wongsakul, existed mainly on his ID card and birth certificate, barely more relevant to daily interaction than his blood type.

Thai naming conventions flip Western assumptions about formality and identity. What seems casual by Western standards—using first names everywhere—is actually the proper, respectful approach in Thailand. Meanwhile, what Thais consider truly intimate—their nicknames—can sound absurdly informal to foreign ears. Understanding this system isn't just about avoiding social missteps; it's a window into how Thai culture constructs identity, hierarchy, and relationships differently than most Western societies.

"Thai naming conventions flip Western assumptions about formality and identity. What seems casual by Western standards is actually the proper, respectful approach."

Every Thai person navigates daily life with three distinct names, each serving a different social function. There's the formal first name—often long, melodious, laden with meaning—chosen carefully by parents or monks. There's the surname, legally required but socially peripheral. And then there's the nickname, short and often whimsical, which is what actually gets used in most of life's interactions.

Take someone named Pattarapong Rattanawong, nicknamed "Toy." At the hospital where he works as a doctor, colleagues and patients call him "Maw Pattarapong"—doctor plus first name. His business cards often display "Pattarapong" in large type, with "Rattanawong" smaller below. But his friends call him "Pee Toy" (big brother Toy), his family just "Toy," and his girlfriend might have her own special variation. His surname? It appears on his medical license and government documents, but you could work alongside him for years without ever knowing or using it.

This isn't informality—it's a sophisticated system where names mark different degrees of familiarity and respect. The formal first name occupies the middle ground: respectful but personal, appropriate for professional contexts and initial introductions. The nickname signals friendship, warmth, the transition from acquaintance to familiar. And the surname? It exists mainly for bureaucracy, a relatively modern addition to Thai naming culture that never quite took root in daily social life.

Thai first names carry weight that surnames never acquired. Parents choose them with meticulous care, often consulting monks or astrologers to find names with auspicious meanings that align with the child's birth details. These names frequently derive from Sanskrit or Pali, carrying meanings like "golden one" (Thongchai), "beautiful" (Sumalee), "wisdom" (Panida), or "brave" (Wira). They're gender-specific, musically composed, and can be quite long—three or four syllables is common.

What throws Westerners is that these formal, meaningful names get used in contexts we'd consider casual. Your Thai colleague introduces herself as "Khun Siriporn" at a business meeting—not "Ms. Boonjinda" or "Mrs. Boonjinda." The honorific "Khun" (roughly equivalent to Mr./Ms./Mrs., but gender-neutral) combined with the first name is the standard respectful address in professional settings, customer service, and any situation where politeness matters.

This creates a fascinating middle ground that doesn't quite exist in Western naming culture. "Khun Siriporn" is simultaneously respectful and personal. It acknowledges her as an individual—using her chosen, meaningful name—while maintaining proper social distance through the honorific. It's more formal than using her nickname would be, but far more personal than hiding behind a family name that might be shared by thousands of unrelated people.

In professional settings: Use "Khun" + first name for everyone until invited to use nicknames. "Khun Somchai" for your colleague, "Khun Siriwan" for your dentist, "Khun Prasert" for your landlord. This is always safe and shows proper respect.

Never use: The surname alone or with Western titles. "Mr. Wongsakul" sounds bizarre to Thai ears—you're essentially calling someone by an arbitrary family identifier rather than their actual name.

On business cards: Notice that first names are typically larger or bolded, with surnames in smaller type below. This isn't a design accident—it reflects how names actually function in Thai society. When you exchange cards, reference their first name in conversation.

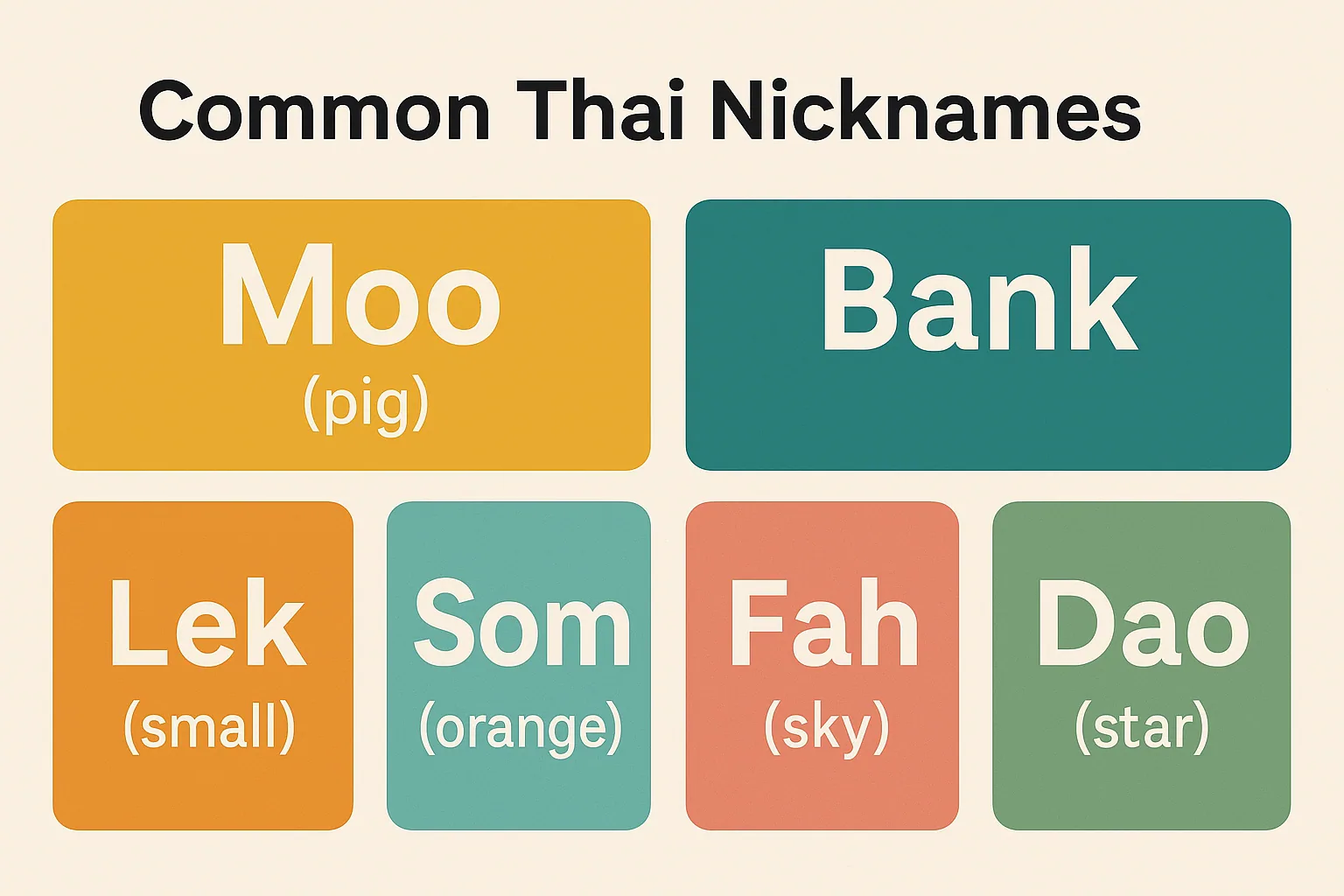

And then there are the nicknames—chue len in Thai, literally "play name." These are what make Westerners do double-takes. While formal names carry gravitas and meaning, nicknames are delightfully random, often single-syllable, and sometimes laugh-out-loud surprising. You'll meet adults named Moo (pig), Gai (chicken), Lek (small), Yai (big), Nok (bird), Pla (fish), Aum (fat), or Toy (tiny). Animal names aren't considered demeaning—they're affectionate, the linguistic equivalent of a warm hug.

Modern Thai nicknames increasingly borrow from English: Bank, Book, Boss, Benz, Beer, Film, Golf, Pepsi, even Hamburger. Some Thais choose nicknames related to their formal names (someone named Pornchai might be nicknamed "Por"), while others seem to have arrived at their nicknames through family jokes, childhood incidents, or pure whimsy. Unlike Western nicknames that often emerge organically from peer groups, Thai nicknames are typically given by parents shortly after birth and stick for life.

These nicknames create an entire parallel social layer. When Thai colleagues transition from "Khun Somsak" to inviting you to call them "Pee Bank" (if they're older) or just "Bank" (if close in age), that's a meaningful shift. You're moving from professional acquaintance to genuine friendship. This invitation should be appreciated—it's an opening of social doors, permission to enter a more intimate circle. Many expats maintain dual-address systems: "Khun Somchai" in meetings, "Pee Chai" at lunch.

→ Animals: Moo (pig), Gai (chicken), Pla (fish), Nok (bird), Maew (cat)

→ Physical traits: Lek (small), Yai (big), Dam (black), Aum (fat), Pueng (bee)

→ English words: Bank, Golf, Benz, Boss, Film, Book, Boss, Pepsi

→ Nature elements: Som (orange), Fah (sky), Dao (star), Nam (water)

→ Numbers: Neung (one), Song (two), especially for birth order

→ Sounds: Pim, Pop, Ping, Pong, Boom, Bam

Thai surnames are historical accidents that never quite found their social purpose. King Rama VI made them legally mandatory only in 1913, part of his modernization campaign to make Thailand legible to Western powers. Each family was required to create a unique surname—no duplicates allowed across the entire nation. This produced the long, elaborate surnames you see today: Rattanawong, Boonsuebprasert, Chaiyapreechawit. These names often incorporate auspicious words or reference the family's place of origin, but they're so unwieldy that they never displaced the established pattern of using first names in social interaction.

Because each surname must be unique, they can't function as they do in the West—as markers of extended family networks or lineage. You can't assume that two people named "Smith" might be related, but in Thailand, any two people sharing a surname are almost certainly from the same family, probably closely related. This makes surnames useful for genealogy but largely irrelevant for daily social navigation. They appear on official documents, government IDs, contracts, and birth certificates, but rarely enter conversation.

Thai law regarding women's surnames has shifted over time. The original 1913 Surname Act allowed women to choose whether to keep their maiden name or adopt their husband's surname. However, from 1941 to 2005, women were required by law to take their husband's surname upon marriage. The current law—since 2005—allows spouses to choose whose family name to use, or for each to keep their own; the change followed a 2003 Constitutional Court ruling on gender equality. Regardless of their legal surname, women continue to be addressed by their first names in all social contexts. "Mrs. Wongsakul" as an address form simply doesn't exist in Thai culture—she remains "Khun Siriporn" whether single or married, at work or at home.

The real sophistication in Thai naming comes from the system of relational titles based on age and status. These small words—prepended to names or used alone—navigate you through Thailand's hierarchical social landscape. The most common are "Pee" (พี่, older sibling) and "Nong" (น้อง, younger sibling), but the system extends to create familial warmth in relationships that have nothing to do with actual family.

When you first meet someone Thai in a casual context, there's often an implicit age calculation happening. If they're older—even by a single year—they become "Pee [Name]" to you, and you become "Nong [Name]" to them. This isn't stuffy formality; it's creating comfortable social order. "Pee" carries connotations of guidance, protection, someone who has your back. "Nong" implies someone you look after, mentor, protect. The terms create pseudo-familial bonds that smooth social interaction.

This explains why Thais often ask your age shortly after meeting you—they need this information to properly address you. It's not rudeness; they're gathering essential social navigation data. Once they establish you're older, you become "Pee" to them automatically. This system extends beyond names: you can call a older shopkeeper "Pee" without using their name, or a younger service worker "Nong," creating instant rapport through these familial terms.

Pee (พี่) - Older sibling: Use for anyone older than you, from peers just a year older to people decades your senior. "Pee Somchai" or just "Pee" alone. Shows respect while maintaining warmth. This is your default when unsure.

Nong (น้อง) - Younger sibling: Use for anyone younger than you. "Nong Lek" or just "Nong." Creates affectionate, protective relationship. Thais might call you "Nong" if you're younger, which should be taken as endearing.

Lung (ลุง) / Pa (ป้า) - Uncle/Aunt: For people your parents' generation. "Lung Somchai" for older men, "Pa Noi" for older women. Common for older shopkeepers, neighbors, anyone significantly older. Shows deeper respect than Pee.

Ta (ตา) / Yai (ยาย) - Grandfather/Grandmother: For elderly people. "Ta" for older men, "Yai" for older women. The most respectful familial terms, typically for people your grandparents' age. Can be used alone or with names.

Some titles override the age-based system entirely, reflecting the deep respect Thai culture holds for certain professions. Teachers in schools are typically addressed as "Kruu" (ครู) plus their first name, while "Ajarn" (อาจารย์) is standard for lecturers and professors at universities, as well as masters and experts in various fields. These titles stick for life; a former student meeting their teacher decades later will still use the appropriate title, never just "Khun." These words carry weight that transcends the teaching relationship itself, acknowledging the sacred duty of transmitting knowledge in Buddhist tradition.

Doctors are "Maw" (หมอ) plus first name—"Maw Pattarapong." This applies to medical doctors and dentists (who are called "Maw Fan" or tooth doctor in casual speech). PhD holders use the title "Doctor" (ดร.), which is distinct from the medical "Maw." Lawyers might be addressed as "Thanai Khwam" in formal contexts, though "Khun" plus first name is more common in practice. Monks follow an entirely different system: "Phra" for ordinary monks, "Luang Por" (venerable father) for senior monks, with their religious names used rather than their lay names.

These professional titles matter in ways that can surprise expats. Using "Kruu" for a school teacher, "Ajarn" for a university lecturer, or "Maw" for a doctor isn't optional politeness—it's acknowledging their social position and the years they invested in earning those titles. Defaulting to "Khun" instead can read as either ignorance or subtle disrespect. When in doubt, if someone has a professional title, use it.

Thailand's nobility system adds another layer of complexity, though you're less likely to encounter it daily. Royal descendants carry titles that prefix their names: M.C. (Mom Chao) for grandchildren of a king, M.R. (Mom Rajawongse) for great-grandchildren of a king, and M.L. (Mom Luang) for great-great-grandchildren of a king. These titles denote the fixed generational distance from the royal ancestor, not from the current reigning monarch. They aren't ceremonial—they're legal parts of the name and must be used. "M.L. Siriporn," never just "Khun Siriporn" if she holds such a title.

Similarly, individuals who have received royal honors carry titles. Married women who receive honors from the Order of Chula Chom Klao may use "Khunying" (for lower classes of the order, roughly equivalent to "Lady") or "Thanphuying" (for higher classes, equivalent to "Dame"). These appear on business cards, in formal introductions, and official documents. If you're unsure whether someone has such a title, their business card will tell you. In Thailand's status-conscious culture, using someone's noble or honor title when they have one shows cultural awareness and respect. For more on navigating Thailand's monarchy and its social implications, see our detailed guide.

Thais are remarkably forgiving of foreigners fumbling their naming conventions. If you call someone "Mr. Wongsakul" instead of "Khun Somsak," they'll likely smile and gently correct you. What matters more than perfect execution is showing you've made an effort to understand and respect Thai cultural norms. A genuine attempt to use "Khun" with first names, or asking "Should I call you Pee?" demonstrates cultural awareness that Thais appreciate deeply.

As a foreigner in Thailand, you'll navigate this system from an interesting position. Thais will typically address you as "Khun [Your First Name]"—applying their cultural system to you. If you're American, you might be "Khun John" or "Khun Sarah." This can feel simultaneously too formal (they're using your first name!) and too casual (but with a formal title!), but it's simply how Thais extend their naming conventions across cultures.

As you build friendships, Thai friends may give you a Thai nickname—usually a shortened version of your name or something that suits your personality. This is an honor, a sign you've been adopted into Thai social patterns. My friend Michael became "Mee," Jennifer became "Jen," and one unfortunately tall friend became "Yai" (big). Accept these nicknames gracefully; they signal that you've crossed from outsider to insider.

You can also adopt the Pee/Nong system with Thai friends once you're comfortable with it. Calling an older Thai friend "Pee" or being called "Nong" by someone older creates warmth that transcends language. It signals that you understand and accept Thai social structures rather than insisting on Western individualism. This doesn't mean abandoning your identity—it means showing respect for the cultural context you've chosen to inhabit.

The beauty of Thai naming culture is how it creates layers of social intimacy while maintaining clear hierarchies. From the respectful distance of "Khun Somchai" to the familial warmth of "Pee Toy," from professional recognition in "Kruu Siriporn" or "Ajarn Pattana" to the multigenerational respect of "Lung Prasert"—each form of address communicates relationship, status, and care simultaneously. For expats, learning these forms isn't about memorizing rules; it's about seeing how language constructs community. Understanding more about Thai body language and customs will deepen your cultural fluency even further.

Names are never just names—they're how cultures construct identity and relationship. In Thailand, where first names carry meaning, surnames gather dust, and nicknames signal intimacy, you're not just learning vocabulary. You're learning how Thai culture values personal connection over family lineage, how it creates hierarchy through age rather than clan, how it builds warmth through familial terms extended far beyond blood relations. Get someone's name right—really right, in the Thai way—and you're speaking more than words. You're speaking the language of respect, relationship, and belonging.

COMMON TITLES

Khun (คุณ)

Formal, respectful. Use with first names in professional settings.

Pee (พี่)

Older sibling. For anyone older than you in casual contexts.

Nong (น้อง)

Younger sibling. For anyone younger than you.

Lung (ลุง) / Pa (ป้า)

Uncle/Aunt. For people your parents' age.

PROFESSIONAL

Kruu (ครู)

School teachers. Used for life.

Ajarn (อาจารย์)

University lecturers, professors, experts. Used for life.

Maw (หมอ)

Doctor, dentist, medical professionals.

Golden Rule

When in doubt, "Khun" + first name is always safe and respectful. Never use surnames alone.

Animal Names

Moo (pig), Gai (chicken), Nok (bird), Pla (fish)

English Words

Bank, Golf, Boss, Benz, Film, Beer

Physical Traits

Lek (small), Yai (big), Dam (black)

Nature

Som (orange), Fah (sky), Dao (star)

At Work

"Khun Somsak" (formal) or "Pee Bank" (nickname, if friendly)

With School Teacher

"Kruu Siriporn" (always use title)

With Professor

"Ajarn Pattana" (always use title)

With Doctor

"Maw Pattarapong" (professional title required)

Older Neighbor

"Lung Prasert" or "Pa Noi" (uncle/aunt terms)